While most of my life has been dedicated to studying for my qualifying exams, finishing up a few book chapters, and working for the City of West Hollywood, I am constantly thrilled for the opportunity to step away from it all and engage in these thought provoking conversations. I hope you enjoy this blog and visit the Feminism and Religion Project to view the new conversation occurring in the field.

____________________________________________________________________

The most disturbing part of the 2006 documentary Deliver Us from Evil isn’t that fact that Father Oliver O’Grady is rewarded by the Catholic church with a new congregation in Ireland after his short stint in prison for the rape of dozens of children in the 1970s but rather the hierarchy of gendered victimization which is often created throughout the various rape cases that both are reported and unreported throughout history.

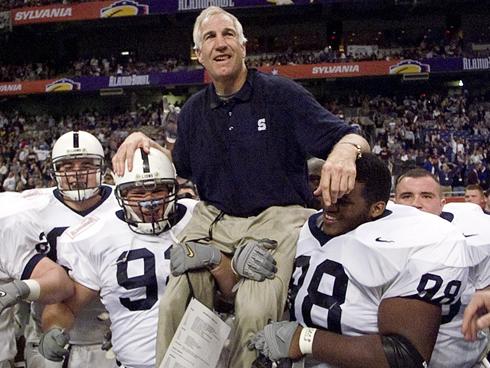

I am often troubled by the ways in which rape cases are discussed and even deconstructed via the mediums such as blogs, online communities, social media networks, the news, and popular culture. No series of events troubled me more than the Jerry Sandusky trial but more importantly, the ways in which the young boys and adult men who were subjected to Sandusky’s abuse quickly overshadowed the other rape cases that are reported on a daily basis, specifically those involving young girls and women.

Our country needs to have a serious conversation about the ways in which masculinity is not only constructed but also deconstructed through the acts of rape, incest, sexual assault, domestic violence, and virility. How do these horrific actions pinpoint and break apart the depiction of the hegemonic and virile man who is impenetrable. How do these acts, which have historically occurred throughout time, gain greater significance in our 24hr news cycle, tech obsessed culture?

Although the rape of a women on a bus in India by six men didn’t go unnoticed by the world, I have to wonder what would have happened if her story would have occurred on November 4th, 2011, the date when a grand jury, who had convened in 2008, indicted him on 40 counts of sex crimes against young boys. Would it have gotten the same amount of attention it did when it came across U.S. news screens on December 16th, 2012? Would the outcry from women across the world silence those of both Penn State as well as various other sports fans and individuals from across the United States?

What these events and society’s obsession with them for the weeks and months and even year after signify isn’t that more attention is being given to violent sexual crimes against all types of bodies but rather a resignification of the hierarchy that is already all too present within our culture today: stories about men in all forms get top billing.

Upon asking a small groups of friends whether or not they have heard about the rape case involving the Indian woman on December 16th, 2012 or even the rape of an elderly bird-watching woman in Central Park in September 2012 the resounding silence pinpointed the reasons why, when asked whether or not they had heard about Jerry Sandusky, their answers were an unequivocal yes.

While the activist in me wanted to cry out and scream “Are you serious!” the scholar in me knew to take a step back and examine the situation from various angles.

Why are violent crimes against women cast aside in light of new stories that involve men sexually or violently abusing young boys or other men? What about masculinity makes it seem both impenetrable and innately hegemonic?

While we could reduce the actions down to the violent response men have when any form of their power and social/sexual status is threatened, we have to step back and examine the issue about the innate power that men are endowed with not only through social institutions but also religious ones as well.

Men are seen as “on top” both figuratively and literally throughout the various images that bombard both young girls and boys immediately from the expulsion of their mother’s womb (and some would argue even before their expulsion). From early on, young boys are taught that they are #1 and that “the other,” i.e., the young girl, is not only below them but also an object that they must possess, whether through violent action or the eternal dance of courting. However, when there is a disruption to this innate system of power structures, the response that we often see is one of violence. While men are taught that they should not show emotion or deviate from the heteronormative society acted out in front of them on a daily basis, their crisis of masculinity often comes with the inability to negotiate what their identities as men actually mean to themselves personally. Giving men the ability and space to discuss what their masculinity means to them creates the opportunity to change the narrative of “men on top.” From small ripples of change that eventually overtake the mainstream current, deconstructing masculinity during times when violent actions are inflicted upon male bodies creates a new chance for scholars and activists to draw attention to not away from the victims at hand but rather into the larger narrative of social, sexual, and domestic violence that occurs all around the world every day to all types of bodies.

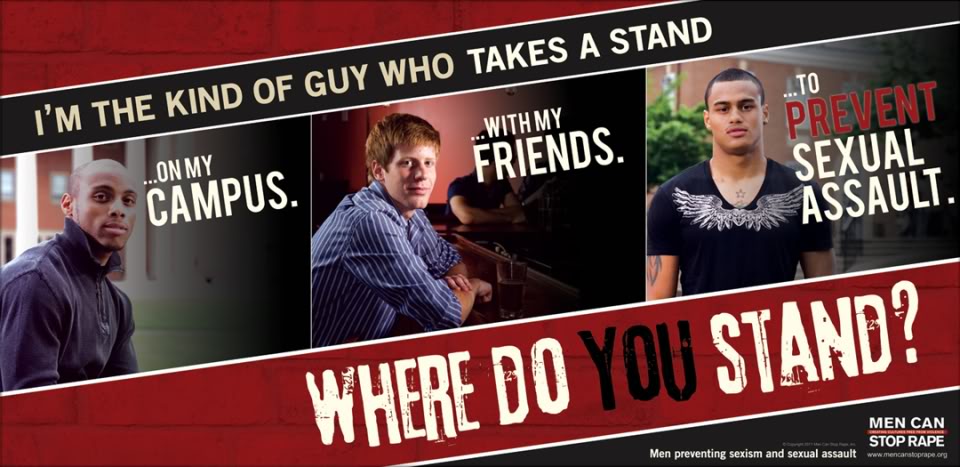

Deconstructing masculinity isn’t the key to solving social, sexual, and domestic violence across the world but it is a step worth taking when attempting to engage men in affecting change to stop these violent actions since men, statistically are the perpetrators of such crimes that both cause such outcry as well as perpetual silence.

(I was fortunate enough to get to spend some time this month talking with Dr. Gina Messina-Dysert at lengths about our lives, our careers, and like with most scholar/activists eventually about the topics we are passionate about. Always a source of inspiration, Gina frequently helps me hash out the many topics I’m interested in writing about and pointing me in the right direction. This post (and the blog it is housed on) would not be possible without her continual presence as a force for change and progress within Feminist and Religious communities.)